By Lori Kurtzman

The Columbus Dispatch

Mention that you’ve scanned an Egyptian mummy, and it seems the International Skeleton Society gets a little excited. Dr. Joseph Yu found his presentation quickly accepted to the society’s fall meeting in Philadelphia, and he’s willing to bet his salary that his will be among the most-popular talks.

That’s the thing about mummies.

“They’re interesting. Everybody loves them,” said Yu, a professor of musculoskeletal radiology at Ohio State University. “They’re so full of information.”

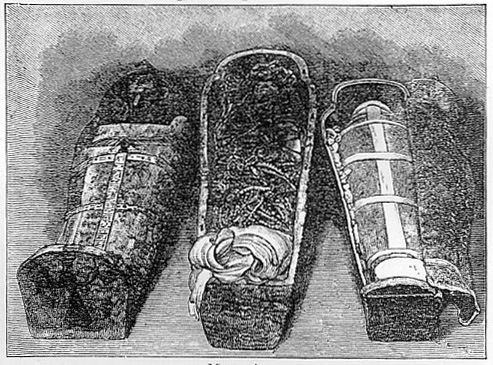

Yu leapt when the Ohio Historical Society contacted the university to see whether someone would scan its museum’s mummy. The ancient woman, believed to be at least 2,500 years old, had been X-rayed in 1930 and 1984, but no one could find the film from those scans.

Now, Yu had access to what he called the “Lamborghini of scanners,” which could evaluate the mummy down to the millimeter, creating three-dimensional images of the woman masked for centuries by bandages. A nice change of pace from the usual patients who undergo CT scans.

“I thought it would be a tremendous opportunity to spread our wings (and look at) something that’s not necessarily life-threatening,” he said.

In June, technicians spent nearly two hours scanning the mummy at Ohio State’s Wexner Medical Center. They winnowed down 100,000 images to about 8,400 images that they pored over for months. Yu said it’s like watching a movie again and again — something previously unnoticed pops up each time. “There’s nothing like a mummy to make normal anatomy really fun again,” he said.

Researchers have employed CT scanners to uncover secrets of both the past and the present. A few years ago, they used scans and DNA testing to determine that Egypt’s famed King Tutankhamun likely walked with a cane, had a cleft palate and died after he broke his leg and contracted malaria.

And last month, scholars who studied 137 mummy scans presented findings at an American College of Cardiology meeting that showed that hardening of the arteries was common, especially among older individuals. The suggestion: Heart disease might have more to do with aging than with poor diet. Mummies didn’t exactly have access to Big Macs.

“We’re studying the many ways that humans have been in the past and may choose to be in the future,” said Andrew Wade, an anthropologist at the University of Western Ontario.

“We get to learn about ancient health and the history of medicine and disease ... (and) what it is to be human.”

Wade is so intrigued by the study of mummies that he has been working for the past five years to build a worldwide database of their scans, beginning with Egyptian mummies. There are thousands of such mummies in known collections and likely a great deal more in private collections, not to mention inside Egypt itself, Wade said.

Most haven’t been scanned. So far, the database, set to launch this year, has 100 human mummy scans with the promise of 100 more.

At Ohio State, the unusual scans are still a novelty. On a recent day, a doctor poked his head into a room where lead 3-D technologist Darlene Meeks had scans pulled up on three computer screens. One showed a body swathed in cloth, another a close-up of the skull with a hollow pathway where the brain had been pulled from the head.

“Oh,” the doctor said, “are you doing the mummy?”

Yu said enthusiasm for the project continues to escalate, especially as researchers learn more about their subject.He watched as Meeks ran a short animated video in which the viewer goes deep into the mummy’s nose to the back of the skull. Another click, and she was flying through the tunnel created by the mummy’s clenched left hand.

She clicked on scans of the mummy’s mouth: “This is an amazing set of teeth,” Yu said. And her back: “Beautiful-looking spine.”

This woman is 2,500 years old, maybe older, and yet she’s easily recognizable. Her anatomy is the same as ours, Yu said. But she comes with both a mystery — museum curators don’t know who she is — and a story, told through the bones and tissue she left behind.

“Most people, when they think about mummies, they think about the scary part from science fiction” movies, Yu said. “But they all once upon a time were living beings ... they give us a very informative, retrospective view of what the past was.”

Joseph Yu will speak about the mummy findings at 2 p.m. on April 26 at the Ohio History Center, 800 E. 17th Ave.

lkurtzman@dispatch.com

http://www.dispatch.com/content/stories/science/2013/04/14/1-scans-reveal-detailed-clues-to-mummys-past.html

By Lori Kurtzman

The Columbus Dispatch

Mention that you’ve scanned an Egyptian mummy, and it seems the International Skeleton Society gets a little excited. Dr. Joseph Yu found his presentation quickly accepted to the society’s fall meeting in Philadelphia, and he’s willing to bet his salary that his will be among the most-popular talks.

That’s the thing about mummies.

“They’re interesting. Everybody loves them,” said Yu, a professor of musculoskeletal radiology at Ohio State University. “They’re so full of information.”

Yu leapt when the Ohio Historical Society contacted the university to see whether someone would scan its museum’s mummy. The ancient woman, believed to be at least 2,500 years old, had been X-rayed in 1930 and 1984, but no one could find the film from those scans.

Now, Yu had access to what he called the “Lamborghini of scanners,” which could evaluate the mummy down to the millimeter, creating three-dimensional images of the woman masked for centuries by bandages. A nice change of pace from the usual patients who undergo CT scans.

“I thought it would be a tremendous opportunity to spread our wings (and look at) something that’s not necessarily life-threatening,” he said.

In June, technicians spent nearly two hours scanning the mummy at Ohio State’s Wexner Medical Center. They winnowed down 100,000 images to about 8,400 images that they pored over for months. Yu said it’s like watching a movie again and again — something previously unnoticed pops up each time. “There’s nothing like a mummy to make normal anatomy really fun again,” he said.

Researchers have employed CT scanners to uncover secrets of both the past and the present. A few years ago, they used scans and DNA testing to determine that Egypt’s famed King Tutankhamun likely walked with a cane, had a cleft palate and died after he broke his leg and contracted malaria.

And last month, scholars who studied 137 mummy scans presented findings at an American College of Cardiology meeting that showed that hardening of the arteries was common, especially among older individuals. The suggestion: Heart disease might have more to do with aging than with poor diet. Mummies didn’t exactly have access to Big Macs.

“We’re studying the many ways that humans have been in the past and may choose to be in the future,” said Andrew Wade, an anthropologist at the University of Western Ontario.

“We get to learn about ancient health and the history of medicine and disease ... (and) what it is to be human.”

Wade is so intrigued by the study of mummies that he has been working for the past five years to build a worldwide database of their scans, beginning with Egyptian mummies. There are thousands of such mummies in known collections and likely a great deal more in private collections, not to mention inside Egypt itself, Wade said.

Most haven’t been scanned. So far, the database, set to launch this year, has 100 human mummy scans with the promise of 100 more.

At Ohio State, the unusual scans are still a novelty. On a recent day, a doctor poked his head into a room where lead 3-D technologist Darlene Meeks had scans pulled up on three computer screens. One showed a body swathed in cloth, another a close-up of the skull with a hollow pathway where the brain had been pulled from the head.

“Oh,” the doctor said, “are you doing the mummy?”

Yu said enthusiasm for the project continues to escalate, especially as researchers learn more about their subject.He watched as Meeks ran a short animated video in which the viewer goes deep into the mummy’s nose to the back of the skull. Another click, and she was flying through the tunnel created by the mummy’s clenched left hand.

She clicked on scans of the mummy’s mouth: “This is an amazing set of teeth,” Yu said. And her back: “Beautiful-looking spine.”

This woman is 2,500 years old, maybe older, and yet she’s easily recognizable. Her anatomy is the same as ours, Yu said. But she comes with both a mystery — museum curators don’t know who she is — and a story, told through the bones and tissue she left behind.

“Most people, when they think about mummies, they think about the scary part from science fiction” movies, Yu said. “But they all once upon a time were living beings ... they give us a very informative, retrospective view of what the past was.”

Joseph Yu will speak about the mummy findings at 2 p.m. on April 26 at the Ohio History Center, 800 E. 17th Ave.

lkurtzman@dispatch.com