domingo, 25 de diciembre de 2011

viernes, 23 de diciembre de 2011

Sancho de Castilla murió probablemente de neumonía

Investigadores de la Universidad Complutense de Madrid (UCM) junto con el Servicio de Anatomía Patológica y Urología del Hospital Clínico de Barcelona y la Universidad de Barcelona revelan que Sancho de Castilla, vástago ilegítimo del rey Pedro I de Castilla (1350-1369), no murió envenenado sino por una neumonía.

Aspecto general de la momia de Sancho de Castilla, vestida con un hábito de lino y un cíngulo de cuero. Los huesos de las piernas se encuentran desarticulados en el regazo. La hemicara izquierda estaba muy bien conservada, reconociéndose incluso el párpado y las pestañas. También conservaba gran parte del cuero cabelludo. Imagen: UCM.

UCM|22 diciembre 2011 12:41

El pasado día 10 de diciembre se presentó al público la restauración de las bóvedas del monasterio de Santo Domingo el Real de Toledo. Este convento alberga los restos mortales de don Sancho de Castilla y Sandoval (1363 – 1371).

De entre la larga prole de vástagos ilegítimos del rey Pedro I de Castilla, la figura de don Sancho ha despertado desde hace años un destacado interés en los investigadores de las más diversas áreas científicas. Su biografía, envuelta en las trágicas circunstancias del complejo momento político que le tocó vivir, ha sido recientemente reconstruida por Francisco de Paula Cañas Gálvez, profesor del Departamento de Historia Medieval de la Universidad Complutense de Madrid.

La labor de investigación realizada por Cañas a través de la consulta de documentación de archivo, en su mayor parte inédita, le llevó a replantearse las verdaderas causas de la muerte de don Sancho. Todos los indicios proporcionados por dicha documentación apuntaban a que la muerte del joven Sancho podría haberse producido por causas naturales y no por la administración de algún tipo de veneno como tradicionalmente se había pensado.

Para confirmar esta hipótesis era necesario realizar un análisis paleopatológico de los restos de don Sancho, conservados en un excelente estado de momificación en el monasterio de Santo Domingo el Real de Toledo.

El primer paso dado por el equipo médico del Hospital Clínico de Barcelona y la Universidad de Barcelona, integrado por Agustín Franco y Jordi Esteban y dirigido por Pedro Luis Fernández, consistió en realizar una inspección externa del cuerpo sin desvestirlo de los dos hábitos dominicos que se le pusieron -el primero, tras su fallecimiento y, el segundo, posteriormente, en 1913-, con el fin de evitar cualquier daño en dichos restos. Las partes visibles eran la cabeza y los huesos desarticulados de piernas y brazos.

Para el estudio endoscópico se usó un uretrocistoscopio flexible y unas pinzas de biopsia con las que se pudieron extraer muestras de ambos pulmones, pleura, nervio óptico, hueso del tarso, cabellos y piel.

La verdadera causa de la muerte

Los resultados científicos del análisis coinciden con los datos biográficos conocidos de don Sancho y confirman las causas naturales de su prematuro fallecimiento. En este sentido es llamativo el volumen de los dos pulmones, en especial el derecho, muy superiores a lo que se podría esperar de un cadáver momificado hace siglos.

Los restos de pigmento antracótico en ambos pulmones podría deberse a una exposición prolongada del sujeto al humo, seguramente de una chimenea, en alguna de las estancias del palacio real de Toro donde pasó sus últimos días. Ello induce a pensar que don Sancho debió de morir durante los meses otoñales o invernales de 1371, recién cumplidos los ocho años, una edad que también confirma este estudio.

Además, la presencia de fibrina, hematíes y macrófagos alveolares con hemosiderina y la ausencia de restos tóxicos metálicos como arsénico, plomo o mercurio, los más frecuentes en los venenos de la época, confirman que la muerte del joven se debió muy probablemente a una neumonía.

Referencias bibliográficas:

CAÑAS GÁLVEZ, Francisco de Paula: Colección Diplomática de Santo Domingo el Real de Toledo. 1 Documentos Reales (1249-1473), Sílex Ediciones, Madrid, 2010.

CAÑAS GÁLVEZ, Francisco de Paula: “Don Sancho de Castilla (1363-1371): Apuntes biográficos de un hijo ilegítimo de Pedro I”, en Homenaje al Prof. D. José Ángel García de Cortázar, Catedrático de Historia Medieval de la Universidad de Cantabria (en prensa).

http://www.agenciasinc.es/Noticias/Sancho-de-Castilla-murio-probablemente-de-neumonia

exámen de monias

Las momias que permanecieron bajo resguardo más de medio siglo, se encuentran en exhibición en el museo Ashmolean de Oxford

Laura Allsop

Sarcófagos y momias con 3,000 años de antigüedad son exhibidos en Gran Bretaña (Museo Ashmolean de Arte y Arqueología/Cortesía).

LONDRES (CNN) — Las antiguas momias egipcias que permanecieron guardadas por más de medio siglo ahora están en exhibición en las nuevas y flamantes galerías del museo Ashmolean de Arte y Arqueología de la Universidad de Oxford.

Los sarcófagos de madera pintados y decorados con cuidado, y los cuerpos envueltos y embalsamados están a la vista en contenedores con temperatura controlada luego de 12 meses de duro trabajo de conservación, junto con una rica colección de artefactos del Valle del Nilo.

Entre los objetos en exhibición está un sarcófago de 3,000 años de antigüedad de un alto clérigo llamado Iahtefnakt, que fue cuidadosamente conservado durante nueve meses antes de ser expuesto.

Pero los artefactos frágiles no solo han recibido trabajo cosmético.

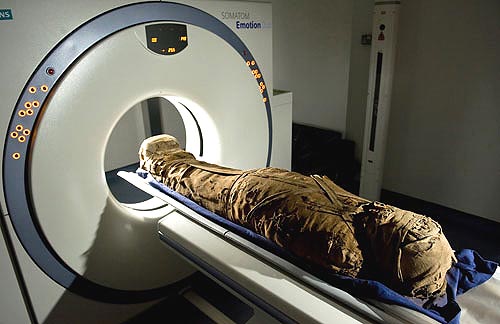

A la momia de un hombre llamado Djeddjehutyiuefankh, que se cree que fue enterrado durante la XXV dinastía (entre los años 712 y 770 antes de Cristo), se le realizó una tomografía en un hospital cercano en Oxford.

El escaneo reveló que tiene amuletos en su boca y accesorios de piedra sobre los ojos, y otro misterio de más de 3,000 años.

“Es intrigante, porque su corazón no está y normalmente esperarías que estuviera en su lugar”, dijo Mark Norman, jefe del área de conservación del museo.

Esto es porque los antiguos egipcios creían que al morir tendrían que realizar un ritual conocido como el pesaje del corazón ante un monstruo en el bajo mundo conocido como el devorador.

Si los corazones eran puros, podían pasar a la siguiente vida; y si no, el corazón debía ser comido.

La causa de la muerte de Djeddjehutyiuefankh no se conoce, pero, según Norman, no hay signos de huesos rotos.

Además del escaneado computarizado, el equipo de conservación realizó un estudio infrarrojo para localizar dibujos debajo de pinturas de la época romana, y utilizaron técnicas forenses para detectar los pigmentos y materiales que pudieron usar los antiguos artesanos.

Esos descubrimientos fueron impresionantes para Normal y el equipo en el museo.

“Nos acercamos al objeto más que nadie desde que éste fue hecho, algo inclusive más cercano, porque usamos un microscopio y mejora de imagen”, dijo.

“El rol de la conservación está cambiando y ahora es mucho más materia de la ciencia forense”, dijo Norman.

El Ashmolean Museum es uno de los principales centros donde se muestra y estudia la antigua era egipcia.

Su colección contiene artefactos que fueron sacados mediante excavaciones por los llamados padres de la arqueología moderna, como Sir William Matthew Flinders Petrie y Francis Llewellyn Griffith, que trabajaron a finales del siglo XIX y a principios del siglo XX.

Incluso tiene objetos obtenidos en excavaciones alrededor del año 1600.

Varios objetos de la colección están en exhibición en las galerías recientemente remodeladas y se incluyen estatuas de piedra caliza de 5,000 años del santuario nubio de Taharqa —el único edificio faraónico en Gran Bretaña— y retratos de momias de la era romana.

Liam McNamara, guardián asistente de la colección del antiguo Egipto y Sudán en el Ashmolean, espera que las galerías, que abrieron al público el pasado sábado, muestren la realidad del antiguo Egipto, y que ayuden a terminar con algunos de los mitos de dicha civilización.

“La realidad del antiguo Egipto es igual de excitante como alguno de los mitos bizarros que han sido creados alrededor de él, y ojalá las nuevas exhibiciones en el Ashmolean inspiren a la nueva generación de egiptólogos”, dijo.

http://mexico.cnn.com/entretenimiento/2011/11/25/las-antiguas-momias-egipcias-reciben-nueva-vida-en-gran-bretana

jueves, 22 de diciembre de 2011

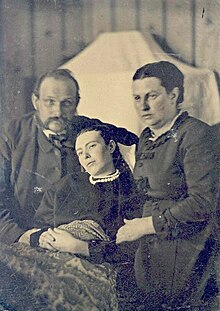

Mememto Mori-imagenes postmortem

http://www.taringa.net/posts/info/854028/fotografia-post-mortem_costumbre-del-siglo-XIX.html

fotografia post mortem.costumbre del siglo XIX

El paso del tiempo siempre conlleva una modificación de las costumbres y, la mayor parte de las veces, el avance científico-técnico. En muchas ocasiones hemos visto como lujos aparentemente inaccesibles se convertían, en unos pocos años, en cosas totalmente comunes al alcance de cualquier bolsillo. Sucedió con la radio, la televisión, los ordenadores… y, hace ya mucho tiempo, con la fotografía (entendida como concepto amplio. A lo largo del artículo hablaremos de la misma como proceso fotoquímico de captación de imágenes, con idependencia del soporte utilizado y sin hacer distinciones entre ellos). Así, a mediados del siglo XIX encargar la realización de un daguerrotipo podía suponer, sin mucho problema, invertir el sueldo de una semana. Posteriormente, ya casi en el siglo XX, solicitar la realización de una foto más o menos tal y como la conocemos ahora seguía resultando bastante caro, aunque el proceso era sensiblemente menos prohibitivo que la toma de daguerrotipos. Si unimos a esto las limitaciones técnicas propias de la época podremos comprender fácilmente por qué resultaba habitual que la mayor parte de seres humanos jamás fueran fotografiados a lo largo de toda su vida, reservándose este tipo de cosas para los actos verdaderamente extraordinarios. En este contexto surgió el tipo de fotografía post mortem.

En primer lugar debemos tener en cuenta que por “fotografía post mortem” en general se entiende toda aquella realizada tras el fallecimiento de un individuo, por lo que es un término que engloba campos tan diversos como la toma de imágenes forenses, el registro de disecciones o la documentación periodística, en algunos casos. Sin embargo, el objeto de este texto no son esas disciplinas, sino las imágenes post mortem tomadas como recordatorio familiar del fallecido, es decir, fotografías encargadas por particulares para su utilización o exhibición privada, en general, dentro del propio hogar. Con esto presente vamos a trazar una historia, muy breve, de un género que fue tan famoso en su tiempo como oscuro y olvidado hoy en día.

el a articulo es muy largo

Yo desde luego no lo haria y creo que lo hubiese hecho! pero ellos decidieron recordar a sus seres fallecidos de esta manera

aqui hay varias fotos

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MU4f6VLTIn8

Este es otro youtube

Los que querian estas fotos querian recordar a su familiar como si estuviera vivo.

Como los padres con su hija

wiki

o los niños que parecen dormidos

antecedentes de las fotos post morten:

AntecedentesEl hecho de fotografiar muertos tiene antecedentes prefotográficos en el Renacimiento, donde la técnica era el retrato por medio de la pintura en el llamado memento mori, frase que deriva del latín, "recuerda que eres mortal" y era utilizado, en lo que a historia de arte se refiere, para la representación de los difuntos; otra técnica de la época medieval donde se concebía que el fin era inevitable y había que estar preparados. La composición de retratos de muertos, especialmente de religiosos y niños se generalizó en Europa desde el siglo XVI. Los retratos de religiosos muertos respondían a la idea de que era una vanidad retratarse en vida, por eso una vez muertos, se obtenía su imagen. En estos retratos se destacaba la belleza del difunto y se conservaba para la posteridad. Los retratos de los niños en cambio eran una forma de preservar la imagen de seres que se consideraban puros, llenos de belleza y eran la prueba misma de que la familia del desafortunado niño, había sido elegida para tener un "angelito" en el cielo.

análisis de los esqueletos del Columbus

Skeletons point to Columbus voyage for syphilis origins

More evidence emerges to support that the progenitor of syphilis came from the New World

Skeletons don't lie. But sometimes they may mislead, as in the case of bones that reputedly showed evidence of syphilis in Europe and other parts of the Old World before Christopher Columbus made his historic voyage in 1492.

None of this skeletal evidence, including 54 published reports, holds up when subjected to standardized analyses for both diagnosis and dating, according to an appraisal in the current Yearbook of Physical Anthropology. In fact, the skeletal data bolsters the case that syphilis did not exist in Europe before Columbus set sail.

"This is the first time that all 54 of these cases have been evaluated systematically," says George Armelagos, an anthropologist at Emory University and co-author of the appraisal. "The evidence keeps accumulating that a progenitor of syphilis came from the New World with Columbus' crew and rapidly evolved into the venereal disease that remains with us today."

The appraisal was led by two of Armelagos' former graduate students at Emory: Molly Zuckerman, who is now an assistant professor at Mississippi State University, and Kristin Harper, currently a post-doctoral fellow at Columbia University. Additional authors include Emory anthropologist John Kingston and Megan Harper from the University of Missouri.

"Syphilis has been around for 500 years," Zuckerman says. "People started debating where it came from shortly afterwards, and they haven't stopped since. It was one of the first global diseases, and understanding where it came from and how it spread may help us combat diseases today."

'The natural selection of a disease'

The treponemal family of bacteria causes syphilis and related diseases that share some symptoms but spread differently. Syphilis is sexually transmitted. Yaws and bejel, which occurred in early New World populations, are tropical diseases that are transmitted through skin-to-skin contact or oral contact.

The first recorded epidemic of venereal syphilis occurred in Europe in 1495. One hypothesis is that a subspecies of Treponema from the warm, moist climate of the tropical New World mutated into the venereal subspecies to survive in the cooler and relatively more hygienic European environment.

The fact that syphilis is a stigmatized, sexual disease has added to the controversy over its origins, Zuckerman says.

"In reality, it appears that venereal syphilis was the by-product of two different populations meeting and exchanging a pathogen," she says. "It was an adaptive event, the natural selection of a disease, independent of morality or blame."

An early doubter

Armelagos, a pioneer of the field of bioarcheology, was one of the doubters decades ago, when he first heard the Columbus theory for syphilis. "I laughed at the idea that a small group of sailors brought back this disease that caused this major European epidemic," he recalls.

While teaching at the University of Massachusetts, he and graduate student Brenda Baker decided to investigate the matter and got a shock: All of the available evidence at the time actually supported the Columbus theory. "It was a paradigm shift," Armelagos says. The pair published their results in 1988.

In 2008, Harper and Armelagos published the most comprehensive comparative genetic analysis ever conducted on syphilis's family of bacteria. The results again supported the hypothesis that syphilis, or some progenitor, came from the New World.

A second, closer look

But reports of pre-Columbian skeletons showing the lesions of chronic syphilis have kept cropping up in the Old World. For this latest appraisal of the skeletal evidence, the researchers gathered all of the published reports.

They found that most of the skeletal material did not meet at least one of the standardized, diagnostic criteria for chronic syphilis, including pitting on the skull known as caries sicca and pitting and swelling of the long bones.

The few published cases that did meet the criteria tended to come from coastal regions where seafood was a big part of the diet. The so-called "marine reservoir effect," caused by eating seafood which contains "old carbon" from upwelling, deep ocean waters, can throw off radiocarbon dating of a skeleton by hundreds, or even thousands, of years. Analyzing the collagen levels of the skeletal material enabled the researchers to estimate the seafood consumption and factor that result into the radiocarbon dating.

"Once we adjusted for the marine signature, all of the skeletons that showed definite signs of treponemal disease appeared to be dated to after Columbus returned to Europe," Harper says.

"The origin of syphilis is a fascinating, compelling question," Zuckerman says. "The current evidence is pretty definitive, but we shouldn't close the book and say we're done with the subject. The great thing about science is constantly being able to understand things in a new light."

Emory University is known for its demanding academics, outstanding undergraduate experience, highly ranked professional schools and state-of-the-art research facilities. Emory encompasses nine academic divisions as well as the Carlos Museum, The Carter Center, the Yerkes National Primate Research Center and Emory Healthcare, Georgia's largest and most comprehensive health care system

Estudio de cráneo

ScienceDaily (Dec. 20, 2011) — Scientists studying a unique collection of human skulls have shown that changes to the skull shape thought to have occurred independently through separate evolutionary events may have actually precipitated each other

Researchers at the Universities of Manchester and Barcelona examined 390 skulls from the Austrian town of Hallstatt and found evidence that the human skull is highly integrated, meaning variation in one part of the skull is linked to changes throughout the skull.

The Austrian skulls are part of a famous collection kept in the Hallstatt Catholic Church ossuary; local tradition dictates that the remains of the town's dead are buried but later exhumed to make space for future burials. The skulls are also decorated with paintings and, crucially, bear the name of the deceased. The Barcelona team made measurements of the skulls and collected genealogical data from the church's records of births, marriages and deaths, allowing them to investigate the inheritance of skull shape.

The team tested whether certain parts of the skull -- the face, the cranial base and the skull vault or brain case -- changed independently, as anthropologists have always believed, or were in some way linked. The scientists simulated the shift of the foramen magnum (where the spinal cord enters the skull) associated with upright walking; the retraction of the face, thought to be linked to language development and perhaps chewing; and the expansion and rounding of the top of the skull, associated with brain expansion. They found that, rather than being separate evolutionary events, changes in one part of the brain would facilitate and even drive changes in the other parts.

"We found that genetic variation in the skull is highly integrated, so if selection were to favour a shape change in a particular part of the skull, there would be a response involving changes throughout the skull," said Dr Chris Klingenberg, in Manchester's Faculty of Life Sciences.

"We were able to use the genetic information to simulate what would happen if selection were to favour particular shape changes in the skull. As those changes, we used the key features that are derived in humans, by comparison with our ancestors: the shift of the foramen magnum associated with the transition to bipedal posture, the retraction of the face, the flexion of the cranial base, and, finally, the expansion of the braincase.

"As much as possible, we simulated each of these changes as a localised shape change limited to a small region of the skull. For each of the simulations, we obtained a predicted response that included not only the change we selected for, but also all the others. All those features of the skull tended to change as a whole package. This means that, in evolutionary history, any of the changes may have facilitated the evolution of the others."

Lead author Dr Neus Martínez-Abadías, from the University of Barcelona, added: "This study has important implications for inferences on human evolution and suggests the need for a reinterpretation of the evolutionary scenarios of the skull in modern humans."

The research, funded by the Wenner Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research (USA) and the Spanish Ministry of Education and Science, is published in the journal Evolution

http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2011/12/111220102248.htm

martes, 20 de diciembre de 2011

lunes, 19 de diciembre de 2011

Momia de Menenra I

The mummy discovered by Gaston Maspero in 1881, while working

at the pyramid of

Merenre I at Saqqara South, presents us with somewhat of a problem with

regard to its identification.

Based on the place where it was discovered, in the black granite

sarcophagus inside the pyramid, it has been identified as belonging to Merenre

I. If this identification is correct, this mummy would be the oldest complete

royal mummy known to us today.

An important part of the problem is the fact that the current

whereabouts o the mummy are unknown, making it impossible to examine it with

more modern tools and equipment than was available in the late 19th and the

early 20th century.

It was reasonably well preserved when it was discovered. The

lower mandible was found missing, as were some of the upper front teeth. The

head was thorn loose from the body. The chest of the mummy was smashed in by

tomb-robbers who were looking for some valuables. The arms of the mummy are

stretched out along the body and, curiously, both feet are spayed outwardly. It

has not been determined whether this position of the feet were a deformity that

the subject suffered in life, or whether the feet were, for an unknown reason,

arranged in this manner by the embalmers, or whether the mummy was just laid in

such a manner by its discoverers prior to it being photographed.

|

momia del National Museum de Belgrado

En el examen de la mandíbula, observaron que el diente molar izquierdo fue extraído en vida. Los incisivos, caninos y premolares fueron fracturados post mortem.

No se observan caries pero si que pudieron constatar la existencia de abrasiones en los dientes, sobre todo en los molares.

Con respecto a los dibujos de los fragmentos de cartonaje hay diversas diosas.

| |||

| | ||

Ya comenté en mi primer post que la historia de la momia comienza en el año 1888 cuando Pavle Ridicki que eraun anciano de 82 años que además era noble,compra la momia en Lúxor.

Ha que recordar que por aquella época, en Lúxor se podian encontrar numrosos objetos que se compraban y eran enviados a diversos países.

Volviendo a nuestro noble, el encuentra entre un montón de piezas de la necrópolis de Akhim, la momia. Después la envía al National Museum de Belgrado para ser expuesta allí.

Después de haber estado el ataúd de la momia en exposición por fin lo abren en mayo de 1993 para poder examinar los restos humanos que contenia.

La momia estaba bastante dañada y comenzaron a examinarla utilizando, claro está medios no destructivos. De la momia quedaba el torso con los brazos y la cabeza , que estaba separada del cuello. También habia parte de las piernes que tambien estaban separadas a la altura de las rodillas.

En el torso habia un agujero a la altura de los hombros e incluso por la parte izquierda podía verse la cavidad toráxica, así es que como veis la momia estaba bastante dañada.

The Scientific study of mummies: pdf

The Scientific study of mummies

domingo, 18 de diciembre de 2011

cancer en momias A.E artículos

CIMAC NOTICIAS: 3 - Mayo - 2007

Aunque no se cuenta con un registro puntual del cáncer a través de

la historia, existen evidencias del conocimiento que de él tuvieron

civilizaciones antiguas. Por ejemplo, los egipcios diferenciaban los tumores

malignos de los benignos, como dejaron asentado en papiros que datan del año

1500 a. C aproximadamente.

Así lo explicó la historiadora Elsa Malvido Miranda en su

conferencia Morir de cáncer, una historia antigua, en la cual hizo un

recuento histórico de esa enfermedad que al parecer es consustancial al ser

humano. Para ejemplificar su persistencia a través del tiempo, mencionó el

diagnóstico de un osteocondroma en un fémur de restos prehistóricos.

Del estudio de los papiros mencionados, se deduce que para los

egipcios el mal no tenía cura y el único tratamiento que existía era un

paliativo, consistente en extirpar o quemar los tumores que brotaban de la

piel, aunque se sabía que después volvían a aparecer en otras partes del

cuerpo.

Otras evidencias del cáncer en el antiguo Egipto son las que

encontró el inglés Augustus Granville, cuando hacia 1825 diseccionó una

momia femenina y determinó la existencia de tumores en los ovarios. En otros

cráneos, pertenecientes a la Dinastías III y V, encontró indicios del

padecimiento, semejantes a los hallados en restos de los años 3500 y 3000

a.C. También identificó tumores malignos en momias de la vigésima Dinastía.

En Persia, en el año 520 a.C., se practicó la curación de un

supuesto tumor de pecho que sufrió Atossa, la esposa de Darío. Aún cuando se

cree que el diagnóstico se confundió con un padecimiento inflamatorio, se le

ubica como un registro antiguo de patología tumoral.

En su recuento, la coordinadora del Seminario de Estudios sobre la

Muerte, del Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia (INAH) explicó que

el médico británico Douglas Darry encontró, en 1909, en una persona

momificada entre los siglos IV y VI a.C. aproximadamente, pruebas de la

enfermedad en el cráneo.

Otras investigaciones en cráneos y en huesos con perforaciones

provocadas, sugieren la existencia de tumores en poblaciones prehispánicas

de Estados Unidos, México y Perú. En Asia, la falta de literatura traducida

a las lenguas de occidente ha dificultado el conocimiento de casos de

cáncer.

Tratamientos

Al referirse a los tratamientos utilizados a lo largo de la historia

para combatir los distintos tipos de cáncer, mencionó la hidroterapia, el

empleo de enemas -líquidos que se introducen por vía rectal en la porción

terminal del intestino-, las dietas especiales, el ejercicio y el uso de la

herbolaria tradicional, de ungüentos y de sanguijuelas.

En los citados papiros egipcios, pudieron identificarse ocho casos

de tumores en pecho de mujeres, los cuales fueron cauterizados con un

instrumento caliente, al que se llamaba "taladro de fuego", utilizado para

destruir el tejido maligno que brotaba. Otro tipo de erupciones externas

también eran extirpadas con un procedimiento quirúrgico similar al que se

practica en nuestros días.

En el papiro egipcio de Ebers ya se contemplaba la hidroterapia como

una práctica habitual. Consistía en la introducción de sustancias líquidas

al intestino a través del ano, tratamiento que médicos ingleses y

estadounidenses recomendaban en el siglo XIX.

La medicina occidental o hipocrática intentaba combatir el exceso de

bilis negra en el cuerpo, que identificaba como la causa del cáncer. Ese

pensamiento de Hipócrates perduró por mil 400 años.

En 1712, Juan de Esteyneffer publicó en México su Florilegio

Medicinal. En este texto se proponía, para mitigar el dolor y evitar que

prosperara el tumor, el uso de sanguijuelas, tomar remedios y aplicar

ungüentos, elaborados con plantas, como la siempreviva, la verdolaga y la

lechuga, además de animales, como ranas verdes y cangrejos de río.

Las recetas de Juan de Esteyneffer contenían además otros

ingredientes poco comunes, como extraer leche de una madre, cocinar el

excremento humano y comer semillas de amapola, entre otros. En algunos

casos, la efectividad del remedio se vinculaba, por ejemplo, a la aparición

de la luna.

En 1913, el doctor John H. Kellogg propuso una alimentación

saludable basada en semillas y hacer ejercicio como medio para evitar la

propagación del cáncer. Actualmente, se vincula a la depresión humana como

inductora del proceso canceroso, toda vez que el organismo se debilita y

queda expuesto a desarrollar diversas enfermedades.

La conferencia Morir de Cáncer, una historia antigua, formó parte de

los trabajos del Taller de estudios sobre la muerte, en el que se abordan

diversos temas en conferencias que van dirigidas a todo el público y que se

realizan cada 15 días, en forma gratuita, en la dirección de Estudios

Históricos del INAH, ubicada en la calle de Allende, número 172, esquina

Juárez, en el centro de Tlalpan.

http://www.cimacnoticias.com/site/07050303-Cancer-companero-d.17469.0.html

José Antonio Garrido

EDWIN Smith fue un notable egiptólogo que desarrolló buena parte de su trabajo en la segunda mitad del siglo XIX. Se formó en los más importantes centros de París y Londres y adquirió gran importancia en el estudio de la lengua egipcia. Pero no sería todo ello lo que le otorgaría honor y renombre sino la adquisición de un papiro a un comerciante de la ciudad de Luxor. El egiptólogo entendió enseguida que este papiro de más de cuatro metros y medio de longitud era un tratado de medicina, pero su sorpresa fue mayúscula al comprobar que lo que tenía entre las manos se estaba convirtiendo en el documento médico más antiguo del que se tenía conocimiento en el mundo, con casi cinco mil años de antigüedad.

El que ha pasado a la historia como el papiro de Edwin Smith demuestra que los egipcios tenían un conocimiento bastante exacto de órganos humanos tales como el corazón, el hígado, el bazo, los riñones y los uréteres, y la vesícula, además de tratar con mucha más racionalidad de la que se les suponía ciertos procedimientos quirúrgicos. Y es que este papiro está formado por un número determinado de casos, que la mayoría de las veces eran lesiones traumáticas que fueron tratadas con cirugía.

Pero hay un hecho que resulta más sorprendente aún y es que en el papiro aparece la primera descripción escrita de un cáncer. En éste se describen ocho casos de cáncer de mama, que son tratados con cauterización, aunque el escrito dice de la enfermedad que "no tenía tratamiento".

Desde entonces, el conocimiento sobre el cáncer ha crecido muchísimo tanto en la detección como en el tratamiento, aunque la enfermedad sigue siendo una de las principales causas de mortalidad en occidente. Según la Sociedad Americana del Cáncer, éste provoca en torno al 13 % de todas las muertes, lo que supone un número próximo a los ocho millones de fallecimientos en el mundo cada año. De todos ellos, más del 90 % están provocados por un proceso denominado metástasis.

Se conoce como metástasis a la diseminación de un tumor primario a otros órganos distantes y sanos. Para que esto ocurra las células cancerígenas tienen que ser capaces de penetrar en los vasos sanguíneos o linfáticos próximos al tumor para acceder a la circulación sanguínea -forzando al sistema circulatorio a producir nuevos vasos, mediante un proceso denominado angiogénesis- e invadir tejidos sanos.

Clásicamente se habla de tumor benigno para referirnos a aquellos que no son capaces de metastatizar a órganos distantes y de tumor maligno, al que sí que es capaz de hacerlo. Es decir, los tumores benignos crecen sólo localmente y por lo tanto es más sencillo su tratamiento, mientras que los tumores malignos son capaces de propagarse, haciendo mucho más compleja la lucha médica contra la enfermedad.

Para que la metástasis ocurra se tienen que dar una serie de reacciones agrupadas en lo que se conoce como cascada metastática, que acaba en la formación de un tumor secundario. Esto sólo es posible si se producen ciertas alteraciones moleculares que dan lugar a la expresión de algunos genes.

Uno de los primeros genes que se vio que estaban relacionados con procesos de metástasis es el que da lugar a la proteína "twist", que se encarga de activar o desactivar ciertos genes. Esta proteína se encuentra disponible en el desarrollo embrionario, donde su función es imprescindible ya que controla la producción y migración de todos los tejidos, pero que desaparece después para permanecer ausente durante el resto de la vida. Pues bien, se ha visto que en un gran número de tumores que acaban metastatizando, esta proteína se encuentra activa.

También el español Joan Massagué, junto a su equipo, ha identificado un paquete de 18 genes implicados en la aparición de metástasis, de los cuales la acción conjunta de sólo cuatro es capaz de desencadenar el proceso. De las proteínas a las que dan lugar estos genes ya se conocía su implicación en procesos inflamatorios y tumorales, pero ahora, además, se sabe de su papel en la diseminación del cáncer.

Y mucho más recientemente, en Diciembre de 2008, un grupo de investigadores británicos publicaba que la expresión de una proteína denominada Fosfolipasa C?1, que está relacionada con la activación de ciertos tipos de lifoncitos -linfocitos Th-, jugaba un papel determinante en procesos de metástasis. El avance de la ciencia en este sentido debe despertar en nosotros moderada ilusión. Es probable que en un futuro a medio plazo se conozcan todos los genes implicados en el cáncer y usar este conocimiento para su tratamiento, pero ese día queda aún en el horizonte.

http://www.elalmeria.es/article/opinion/332248/cancer/egipto/los/faraones.html

El papiro de Adwin Smith y la civilización egipcia y se decarga

en esta página web

http://www.anm.org.ve/FTPANM/online/Gaceta%202002%20Julio-Septiembre/13.%20%20Puigb%C3%B3%20J%20(378-385).pdf

Fresh autopsy of Egyptian mummy shows cause of death was TB not cancerA macabre 19th century autopsy of of the mummy of a 50-year-old woman named Irtyersenu misdiagnosed her cause of death

Ian Sample

The mysterious death of an Egyptian woman, whose mummy became a public spectacle in Georgian Britain, has been solved by a team of researchers in London.

Forensic analysis of tissues taken from the 2,600-year-old corpse has revealed signs of tuberculosis, a disease that was widespread in Egypt.

The mummy of Irtyersenu or "lady of the house" became the first to go under the surgeon's knife in an autopsy in 1825, when England was in the grip of mummy mania.

The remains were unveiled to a large crowd in a macabre lecture by Dr Augustus Granville who, in a theatrical flourish, lit the room at the Royal Society with candles made from wax scraped from the shrivelled corpse.

The examination revealed that Irtyersenu "had very considerable dimensions", was around 50 years old when she died, and had borne several children. Her body was so well preserved, Granville said he could identify the cause of death as ovarian cancer.

The corpse, which has been dated to 600 BC, had been removed from the necropolis in Thebes by a young explorer called Archibald Edmonstone, who had passed it on to Dr Granville to investigate. The autopsy laid the foundations of the scientific study of Egypt's mummies.

Irtyersenu was bought by the British Museum in 1853, but lay forgotten in a storage room until the 1980s when John Taylor, an Egyptologist at the museum, stumbled upon a large chest containing her remains.

Writing in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B, researchers at University College London and the British Museum describe how they performed a modern autopsy on the mummified remains.

Dr Granville was right in identifying ovarian cancer, but the tumour – roughly the size of an orange – was a benign type called a cystadenoma and so could be ruled out as the cause of death.

The researchers, led by Helen Donoghue, analysed tissue from Irtyersenu's thigh bones and hand, and also from her lungs, gall bladder and other organs. The tests revealed the presence of DNA from Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the pathogen that causes TB, in the lungs and gall bladder, and in other tissues that are thought to have come from her diaphragm or from her pleura, the thin membrane that covers the lungs. Further signs of the disease were detected in her thigh bones.

"We are able to enhance the original paper by Granville to the Royal Society by concluding that there is evidence of an active tuberculosis infection in the lady Irtyersenu and that this rather than a benign ovarian cystadenoma, was likely to be a major cause of her death," the authors write.

John Taylor at the British Museum said Irtyersenu provides a rare insight into the health of the ancient Egyptians because her internal organs were preserved so well. "A lot of her organs were present that are not normally found in Egyptian mummies," Taylor told the Guardian.

When wealthy individuals were mummified they usually had their organs removed, with the brain being pulled out through the nose and the rest through an incision in the abdomen. "In this mummy it was totally different. Most of the organs were left inside, so the digestive and reproductive systems and some of her organs were in good condition," Taylor said.

The technique used to preserve Irtyersenu suggests that she was not from the higher social classes, but ornate paintings on her coffin suggest she was not among the poorest either.

The investigation has shed light on another puzzle surrounding Irtyersenu and the public lecture that brought Dr Granville fame in 1825. The doctor believed the woman had been preserved by being submerged in a tank of hot beeswax mixed with bitumen. It was this material he believed he had removed from the corpse to make candles for his lecture.

However, the latest study found no evidence of beeswax or bitumen on Irtyersenu's remains. Instead, the researchers suspect the wax Dr Granville collected was a substance called adipocere, which is produced when fat breaks down in decomposing bodies.

en este enlace hay un link de audio

http://www.guardian.co.uk/science/2009/sep/30/autopsy-egyptian-mummy-tb-cancer

imagenes

una momia romana, posee tinte procedente del plomo de Huelva

HOMINES.COM | [24/08/2007]

Recientes análisis de fluorescencia con rayos X, efectuados por el Museo de Brooklyn, sobre una momia egipcia de época romana denominada ‘Demetrios’, datada entre el año 94-100 de nuestra era, revelan, por su perfil químico, la utilización de plomo proveniente de Río Tinto (Huelva) para la elaboración del pigmento rojo con el que fueron pintadas las vendas de Lino y el sarcófago de madera que envolvían y guardaban a este personaje.

El plomo era utilizado en esta zona, de amplia tradición minera (más de 5000 años)

para la fundición de la Plata, de la que era gran productora en tiempos del Imperio romano.

El escáner confirma que ‘Demetrios’ murió con una edad aproximada de 50 años. Sus huesos muestran poco desgaste o deformación, por ello se le supone una posición acomodada, lejos de los duros trabajos realizados por los esclavos. Además, este tipo de pigmentos de importación, eran productos caros por su exotismo, al alcance de pocos bolsillos. Este tipo de momias pintadas de rojo, son excepcionalmente raras, siendo tan sólo conocidas otras 10 de características similares en el mundo. A diferencia de los hombres, las momias de esta época, de mujeres, es multicolor.

El pigmento así obtenido era altamente tóxico, muy venenoso. Por esto, se piensa que pudieron utilizarlo para proteger de acciones externas como parásitos, al sarcófago y la momia para su preservación.

Cuándo finalicen los estudios sobre ésta y otra momias de animales de la colección del museo, podrán ser visitadas en la exposición que prepara el Museo de Arte de Indianápolis, en la muestra denominada ‘Vivir Siempre’

http://www.homines.com/noticias/20070824.htm

Posible momkia de un hijo de Ramses II

La momia que estaba en el museo municipal ha sido identificada como uno de los hijos de Ramses II (hipótesis confirmaa al 90 por cien)

Pensaban que era una mujer, en concreto una bailarina del templo, pero con los análisis realizados y las pruebas del CT sacan, han confirmado que es posiblemente uno de los 110 hijos de Ramses II.

Piensan que murió sobre los treinta años de edad ( en su treintena) y que está datada la momia entre el 1295 y el 1186, muriendo de una enfermedad ,no por muerte natural.

También han comprobado que n el proceso de su embalsamamiento se utilizaron resina de tomillo y de pistacho, materiales muy caros y que eran usados para la realeza y sacerdotes.

Cuándo descubrieron la momia pensaron que se trataba de una bailarina ya que en el sarcófago había inscripciones y jeroglíficos, pero piensan que la momia fue introducida en un ataúd que no era suyo porque posiblemente robaron el ataúd original.

By Lucy Cockcroft

Last Updated: 2:38am GMT 16/03/2008

An Egyptian mummy kept on display in a provincial museum for nearly 80 years has been identified as a son of the powerful pharaoh Ramesses II.

The 3,000-year-old relic was thought to have been a female temple dancer, but a hospital CT scan showed features so reminiscent of the Egyptian royal family that experts are 90 per cent sure it is one of the 110 children Ramesses is thought to have fathered.

The Bolton Museum mummy was thought for many years

to have been the remains of a female temple dancer

Tests showed that the mummy had a pronounced over-bite and misaligned eyes, akin to members of the 19th Dynasty, and his facial measurements were found to be almost identical to those of Ramesses himself.

Experts believe that the mummified man died in his thirties between 1295 and 1186 BC of a wasting disease, likely to be cancer.

Chemical analysis also showed that the body had been embalmed using expensive materials, including pistachio resin and thyme, the preserve of priests and royalty. The story of the royal mummy was uncovered by a team from York University who were filmed carrying out the tests for History Channel series Mummy Forensics.

Gillian Mosely, the producer, said: "When the mummy was taken away for analysis we thought we were looking at a female temple dancer, we certainly didn't expect to make a significant discovery like this. It has been a very exciting and ground-breaking process.

"After conducting a series of tests, including a hospital scan, we are 90 per cent sure he is a son of Ramesses, and other evidence suggests he was probably also a priest."

The identity of the mummy, kept at Bolton Museum, Lancs, has been hidden because hieroglyphics on its sarcophagus suggested that it was a female temple dancer.

Historians now believe his body was placed in this coffin years after his death either by a grave robber who stole the original sarcophagus, or it was hidden by people hoping to protect it from thieves.

Mummy Forensics is screened tomorrow at 8pm and 11pm on the History Channel.

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/main.jhtml?xml=/news/2008/03/15/wmummy115.xml

traslado de la momia de Nesyamun

By Helen Kane

Easy does it! Nesyamun on a specialist mountain rescue stretcher being moved out of storage to travel the two miles to the museum

Specialist mountain-rescue kit was called in yesterday to move a Yorkshire mummy into its new resting place at the Leeds City Museum in Millennium Square, where he is expected to be a star attraction.

Nesyamun – also known as The Leeds Mummy – was transported from his previous home in storage on Thursday September 4 to the much grander surroundings of the city’s new museum. This is due to open to the public on September 13 2008.

The display will reveal a fascinating history around the ancient Egyptian, who was a priest in Thebes before his second life as celebrity exhibit.

“The Leeds Mummy is one of the most outstanding exhibits in our incredible new museum,” said Cllr John Procter, the council’s executive member for leisure. “We are counting the days till it opens.”

The major operation to move the mummy over two miles to the new museum has also revealed startling new facts relating to his death, which was initially thought to have been caused by strangulation.

A combination of bulging eyes and in particular the protruding tongue in his perfectly preserved face at first led experts to believe that he had been strangled. Embalmers would ordinarily always close the mouth of a corpse. To not have done so suggests that they were unable to.

However, the fact that his hyoid bone is still intact – it supports the tongue and is commonly crushed when pressured – has largely ruled out the likelihood of strangulation.

Experts now believe that a single sting from a small bee or some other venomous insect could have ended his life rather than murder: his face is contorted in a way consistent with a sudden, dramatic death. The insect’s venom is thought to have caused an anaphylactic (allergic) reaction when it stung him, causing a rapid demise.

Visitors to the new museum will also be able to see what the unfortunate Nesyamun’s face looked like. A bust of his head, which shows him as he would have looked back home in Thebes in 1100 BC, will also go on display for the very first time.

Leeds City Council’s curator of archaeology, Katherine Baxter, said: “It is quite controversial to display the mummy himself at a time when other museums are debating whether it is best to cover them up. We have thought long and hard about this and we feel we learn far more about him as a person this way.”

“Our reconstructed tomb is towards the back of the gallery and is designed so that you have to make a conscious decision to go in and look at him. I think that’s far more respectful than just putting him in a glass case – covered or otherwise – in the middle of a room.”

As well as his face, Nesyamun’s hands and feet will also be visible, with the rest of his body loosely covered by linen bandages. His intricately painted sarcophagi will also be in the climate-controlled case with him. Each of them are covered in prayers for his safe passage to the afterlife written in Egyptian hieroglyphs.

“Nesyamun is already known – on the basis of his coffin cases – as one of the finest examples of a mummy in the UK,” added Cllr Proctor. “This new display, which includes for the first time the mummy himself and the fascinating reconstruction of his head, will tell us far more about his life and who he was than we knew before.”

All things considered, Nesyamun’s afterlife has been no less dramatic than his original one.

Having been bought to the city by local banker John Blayds (who purchased Nesyamun and two other mummies in 1823 for the Leeds Philosophical and Literary Society) Nesyamun, as the most important of the three, was moved during the war to avoid air attacks in 1941.

The move proved to be a fortunate one – only a week later, both the old museum and the other two mummies were completely destroyed by bombs.

Leeds has been without a permanent museum ever since and the opening of the new building – housed in the former Civic Institute Grade II listed building in Millennium Square – is a much anticipated addition to the city.

Around £20 million has been spent on the museum which will feature four floors of exhibitions and a large central arena. Funding comprised 75% from the Heritage Lottery fund, with Leeds City Council and Yorkshire Forward being the other main funders.

A Quick lowdown on The Leeds Mummy

Although his teeth are worn down through stones and sand in bread he would have eaten, Nesyamun has no signs of tooth decay thanks to ancient Egypt’s sugar-free diet.

He was a priest at the temple of the Egyptian god Amun in Karnak in ancient Thebes.

Nesyamun is thought to have died in his mid-forties – this would be a decent life-span for an ancient Egyptian as they lived to a maximum age of around 50.

His name means “the one belonging to Amun”.

Scientific studies have found evidence of a variety of health problems – including arthritis, parasitic worms and an eye condition – in his remains.

A 3D bust of the mummy's head produced with a 360° scan will be on display next to the coffin and mummy

Leeds Museums & Galleries curator of archaeology Katherine Baxter installing the mummy in his case alongside the sarcophagi.

http://www.24hourmuseum.org.uk/nwh_gfx_en/ART60517.html

Momia Museo Otago

The face of an Egyptian mummy at Otago Museum has been revealed for the first time in over 2,000 years.

The 35-year-old female aristocrat has been part of the museum's collection for more than a century.

The facial reconstruction of the mummy is the result of over a year's work by a team from Otago University and they are confident that their modern day model is extremely accurate.

"I would say if somebody from that era comes and sees this reconstruction, I would say they would recognise her," says Dr George Dias from Otago University's Adanatomy Department,

The team developed an advanced method of facial reconstruction, which more accurately recreates the soft tissues like nose and skin surrounding the skull.

Previous methods have more guesswork and left the process open to artistic interpretation.

"We know there's no such thing called an average face," says Dr Dias. "You take two people from the same racial background, same age, same sex, the faces are different."

Four years ago, scientists in Egypt put the mummy of Tutankhamen through a CAT scan. There, the fragile skeleton of the young Pharaoh was already unwrapped.

But this new process is non-invasive, preserving the ancient artefact by editing the original CAT scan.

The mummy was then electronically unwrapped, stripping away her wooden sarcophagus, bandages, and remaining soft tissue - revealing an accurate 3D image of the skull inside.

The process also has genuine real world applications, in the area of Police forensics and cold cases.

The next step is using silicone skin, to create a more human face.

http://www.3news.co.nz/News/NationalNews/Whos-your-mummy-High-tech-wizardry-reveals-face-of-ancient-aristocrat/tabid/423/articleID/88775/cat/64/Default.aspx

Momia de Nasihu

Hyderabad, July 29 (IANS) Expert assistance from Egypt is finally on its way to conserve an Egyptian mummy dating back to 2500 BC at a museum here.

The mummy, believed to be of Nasihu, daughter of the sixth Pharaoh of Egypt, is on display at the Andhra Pradesh State Archaeological Museum here since 1930 but is now decaying.

A two member team from the Supreme Council of Antiquities, Egypt will visit Hyderabad for conservation of the mummy, believed to be over 4,500 years old.

The department of archaeology and the Museum of Andhra Pradesh have long been seeking foreign assistance to restore the mummy, one of the six in Indian museums and the only mummy in south India.

Tarek El Awdy, head of the research department at the Supreme Council Antiquities (SCA) and Sama Mohamed El Marghani, Director General of Treatment of Biological Damage at SCA will first make an assessment of the work needed to be done for preservation of Nasihu’s body.

SCA is a part of the Egyptian Ministry of Culture and responsible for the conservation, protection and regulation of all antiquities and archaeological excavations in Egypt. Tarek El Awdy is also the general supervisor of the Egyptian Museum, Cairo.

According to P. Chenna Reddy, director of Archaeology and museum, the linen bandage of the mummy would be replaced. The experts will also replace the existing material stuffed inside the mummy with scientifically treated cotton foam material.

The crust of the body, lying in an airtight enclosure, is fragmenting at the face, shoulders and around the feet. The wrapping has started to peel and the cracks are very conspicuous at several places.

The mummy was brought by Nazeer Nawaz Jung, son-in-law of Mir Mehboob Ali Khan, the sixth Nizam or ruler of then Hyderabad State around 1920. He gifted it to the seventh Nizam Mir Osman Ali Khan, who in turn donated it to the museum in 1930.

The museum located in Public Gardens in the heart of the city was then known as Hyderabad Museum. But after the merger of Hyderabad State with the Indian Union it was renamed the State Archaeological Museum.

http://www.thaindian.com/newsportal/health/egyptian-experts-to-conserve-mummy-in-hyderabad-museum_100224792.html

Momia de Tahemaa

A team of radiographers at a London university have been preoccupied with a patient somewhat older than most - 2,500-year old Egyptian mummy Tahemaa.

Specialists at City University in Islington, north London, used a CT scanner to learn more about how she died without damaging the corpse.

They discovered that, unusually, the brain had been left inside the mummy - suggesting an apprentice embalmed her.

Tahemaa lived in a temple in Luxor, southern Egypt, and died aged about 28.

Jayne Morgan, a senior lecturer in radiography at City University London, led the team.

She said: "It is the first time I have had such an old patient.

"But you suddenly realise you are still scanning a human being - even if it is 2,500 years old.

"You scan it in exactly the same way as a human patient.

"But because the mummy is stationary it gives you less problems with movement."

Ms Morgan said the team's principle emotion was wonder.

"The brain was still completely intact", said Ms Morgan. "We could see a fracture in her leg bone in very fine detail."

The scanner, usually used to train would-be radiographers, is valued at nearly £1m.

It uses radiation to provide high resolution images of the body - and cast fresh light on the "health" of Tahemaa, who is owned by the Bournemouth Natural Sciences Society.

Researchers discovered her thigh bone was broken after death.

Apart from the poor condition of her teeth - shared by many Ancient Egyptians owing to the tough bread they ate - Tahemaa was in good physical condition when she died.

The team were unable to establish what killed her, though they dispelled a previous belief she may have suffered a blow to the face.

A scan carried out 16 years ago showed a mark across the face - but the far more advanced equipment used today revealed it as nothing but fuzz on the image.

http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/england/london/8176784.stm

Tahemaa's ancient rags are in acute contrast with scanner's modern lines

VIDEO

This artist's impression of Tahemaa suggests how she may have looked

Un cuerpo momificado egipcio femenino conocido como "Tahemaa"de 2,500 años de antigüedad, se escanea en el Centro de SaadRadiografía

http://spanish.news.cn/tec/2009-08/02/c_1319244_2.htm

Momia del sacerdote Irethorrou

| |||

|

| ||

La momia del sacerdote Pahat

BMC

By

Jenn Smith

Thursday February 25, 2010

PITTSFIELD -- Though he may be a mummy, the Egyptian priest Pahat can still

speak volumes about his ancient civilization.

On Wednesday morning, the nearly 2,300-year-old Berkshire Museum resident and

the lower half of his sarcophagus were wrapped to brave the winter weather to

undergo a CT scan at Berkshire Medical Center.

The procedure uses advanced X-ray technology as a tool in the scientific

study of mummies.

Stuart Chase, executive director of the museum, was among a crowd of nearly

20 other museum, medical and press personnel who squeezed into BMC's CT scanning

suite to watch the process firsthand.

"It's a rare situation to have a mummy and to be a museum that's so close to

a hospital with the technology to be able to do this," said Chase. "It's an

exciting new way to unlock the mysteries of the past."

Pahat himself was first scanned in 1984. On June 4, 2007, the mummy was

scanned again at BMC.

The 2007 scan was the result of the mummy being chosen as a participant in

the Akhmim Mummy

Studies Consortium (AMSC) research project, which is based in Harrisburg, Pa.

Led by Dr. Jonathan Elias, an Egyptologist and physical anthropologist, the

AMSC's mission is to use mummies to advance knowledge on the ancient city of

Akhmim (formerly Ipu), Egypt, where Pahat was found.

Located about 300 miles south of Cairo, this site contains a vast necropolis

from which dozens of mummies were taken and sold for as little as $5 but shipped

to buyers for as much as $250 during the 1880s. Pahat was procured by Zenas

Crane who founded the Berkshire Museum in 1903.

Collections Manager Leanne Hayden was "very nervous" about the mummy

returning to BMC on Wednesday, for fear of his ancient body being exposed to

outside elements and another dose of radiation from the CT scan.

But the hospital upgraded to a new scanning machine since 2007. Scans can now

be done at a faster rate using a lower dose of radiation and can produce

analysis-ready images at a higher resolution. So Hayden agreed to the mummy's

third scan.

"We're always looking to expand living research at the museum. We're always

finding new things about our own collection. This will give us more information

through the context of Pahat's procedure," she said.

Data from the 2007 scan was used to create a 3-D bust of Pahat, who died

around the age of 50 as a Sem priest to the temple cult of Min, the Egyptian god

of male virility and harvest. Elias called priests like Pahat the "worker bees"

of a temple, often aiding in funerary processes.

The data collected from Wednesday's CT scan will be incorporated with what is

known as "fly-through" animation technology to create a 3-D journey through the

mummy's body cavity. The new images will be unveiled this summer at the premiere

of the museum's exhibit "Wrapped! The Search for the Essential Mummy."

Pahat's latest scan comes amidst the international buzz about another ancient

mummy, King "Tut" Tutankhamen. Last week, new research emerged indicating that

the famous boy pharaoh may have died from complications with malaria.

But Elias feels that the preoccupation with Tut complicates the study and

public knowledge of ancient Egypt as a whole, and the lives of more ordinary

people like Pahat.

"The world needs to move beyond Tut," said Elias. "We have to care about

other Egyptians. Otherwise, science doesn't progress."

http://www.berkshireeagle.com/local/ci_14466448

La momia de Hermione

doors

Rarely-seen treasures from Anglo-Saxon England, Ancient Egypt and the

Mediterranean are being opened up to public view following the refurbishment of

the small museum of Girton College Cambridge.

The Lawrence Room at Girton contains a range of unique pieces including

Anglo-Saxon treasures recovered on the college site in 1881 and, perhaps most

importantly, Hermione Grammatike, a named portrait mummy of a young female

classics teacher from the Fayum city of Roman-era Egypt.

Excavated by William Flinders Petrie during the winter season of 1910/1911 in

the Roman cemetery at Hawara, on the eastern edge of the Fayum, Hermione has

become something of a Girton icon.

The subject of poems and a couple of college plays, she returned to England

as a complete mummy, with her portrait still in place, featuring fine wrappings

which were considered equally noteworthy.

Writing in 1911, Petrie described how rare it was for the names of the people

mummified had been preserved. "The most important of these is that of Hermione

the Grammatike, or teacher of the classics, whose name and title are painted in

white on the ground of the portrait," he explained.

"This is the only instance known of a mummy or portrait of a woman teacher;

it now rests in the library of Girton College."

Several primary school women teachers are known from Roman Egypt but, as a

female teacher at a more advanced level, Hermione Grammmatike is unique.Visitors to the college can discover more about her unique story together

with a wide range of important artefacts and antiquities in state-of-the-art

display cases, with fully-supporting information.

"We are delighted to now be able to provide regular public access to the

Lawrence Room," says College Curator Frances Gaudy. "It is a truly fascinating

collection and quite a hidden treasure.

"It is already of great interest to researchers and academics and we hope

that its new, regular open hours will mean that a far wider audience will be

able to enjoy these pieces."

The Lawrence Room is open to the public every Thursday between

2pm and 4pm, other times by appointment only (please allow at least 24 hours).

For all enquiries and appointments email

http://www.culture24.org.uk/history+%26+heritage/archaeology/art77212

Examen de la momia de Ka-i-nefer

This summer, The Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF), the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, a prominent local cardiologist, and an Egyptian anthropologist have all taken part in a unique collaboration to unearth the secrets of the Museum’s 2,500-year-old Egyptian mummy.

The discoveries, the most prominent of which is a sketch of what the man underneath the wrappings actually looked like, will be revealed to the public in a special presentation today at 1:30 p.m. and 3 p.m. in the Museum’s Atkins Auditorium. (The program is free, although tickets must be reserved through the Museum’s website.)

The findings were unveiled recently at a Museum press conference attended by ATF deputy director Kenneth Melson, as well as Nelson-Atkins curator of ancient art Robert Cohon and Mid America Heart Institute cardiologist Dr. Randall Thompson. “Today, what we’re celebrating is the marriage of art and science,” new Museum director Julian Zugazagoitia said in his opening remarks, the first to the press since beginning his tenure earlier this month.

Indeed, the collaboration seems rather farfetched, almost like something out of an old X-files case. “It’s a bit of CSI and art,” Zugazagoitia remarked, in another T.V. reference. The scientific look at the mummy actually began at the prompting of Dr. Thompson, who was part of a team that examined the CT scans of 20 mummies housed in the Museum of Antiquities in Cairo, Egypt. The group was looking for evidence of heart disease in ancient Egyptians.

Eventually, Dr. Thompson was invited to examine the CT scans and X-rays of the Nelson-Atkins museum, and it was then that he reached out to the ATF for its expertise in composite renderings. “This project really highlights the intersection of forensic science, medicine, art and more uniquely, law enforcement,” said deputy director Melson. ATF Special Agents Sharon Whitaker and Robert Strode used the agency’s EFIT—Electronic Facial Imaging Technique—a computerized composite rendering system, to develop a sketch of the ancient Egyptian man.

Robert Cohon, the always passionate curator of ancient art at the Nelson-Atkins, spoke about the Museum’s motivation in having their mummy—which they acquired from Emory University in 2004 and named Ka-i-nefer, which means, “my vital life force is good”—examined so closely. “Well, first of all, our staff is very curious,” he said. “[Through radio-carbon dating] we were able to come up with a rough date of 525 to 332 B.C. [for the mummy’s death]…It was then that we had the good fortune of meeting Dr. Thompson. And he said ‘Do you mind if I take a look at the X-ray and CAT scans of your mummy?” And we said ‘Please do.’

“He did, and he started coming back with some really cool information, including shoe size. But more than that, he said, ‘Heck, why don’t I introduce you to some people in the ATF? They can help you reconstruct the face.’ And we said ‘Sure, bring them in.’ It was another piece of the puzzle.”

The image that the ATF Special Agents came up with is a rather stark one, with dead, almost criminal eyes, which seems almost appropriate considering the EFIT program renders images for law enforcement purposes. In life, Ka-i-nefer lived to be 45 to 55 years old, stood about 5 feet five inches and wore a size seven shoe (or sandal). He had unusually good teeth and was probably closer to an elite status, although his exact position in society is unknown.

Deputy director Melson pointed out the difficulty in obtaining all of this information. “It’s unlike the typical case…This is where there were no eye witnesses, there were no early photographs of the person for age progression purposes. There were no skulls or other parts to use because, remember, this individual was wrapped in linen.”

The mummy is displayed along with many other Egyptian artifacts, including a stunning coffin and funerary collection, in the Museum’s new Egyptian galleries, which reopened last May. For more information on Ka-i-nefer, and all of the Museum’s treasures, visit their website.

http://www.examiner.com/cultural-events-in-kansas-city/atf-agents-the-nelson-atkins-and-others-collaborate-to-unearth-the-secrets-of-an-egyptian-mummy

http://cdn2-b.examiner.com/sites/default/files/styles/large/hash/55/a8/55a8ee268bd34ac58725745476d223be.jpg

An X-ray of the Nelson-Atkins 2,500-year-old mummy Ka-i-nefer

Photo: courtesy Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art